But Mumbai’s economy is heavily dependent on its over-crowded suburban trains and buses. Mumbai, for example, is the country’s worst-affected city in terms of covid-19 infections. Offices cannot return to regular routines if employees have to use packed buses and trains for their commutes. Air carriers will not be viable if they are asked to keep seats vacant in order to maintain physical distance on board between one passenger and another. Ending the lockdown at a time when there is no vaccine or cure for covid-19 means that social distancing cannot be maintained when people have to travel in jam-packed buses, metro cabins and train compartments. The biggest roadblock to ending the lockdown is actually poor public transport. While this mistake in now widely acknowledged and will be rectified, less acknowledged is the poor investments we made in public transport. Nothing illustrates this better than our low investment in healthcare and education. These current dilemmas are rooted in the poor choices we made in the past.

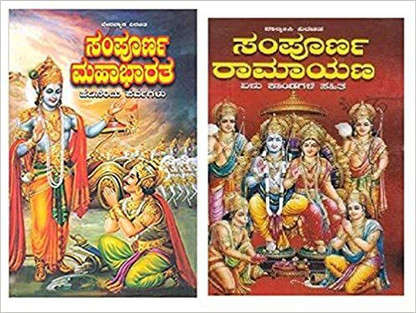

#MAHABHARATA AND RAMAYANA HOW TO#

The dilemma we now face is when and how to lift the lockdown, and what additional health risks we will be courting when we do ease up. India chose to lock down early in its pandemic cycle, and is being criticized for endangering the livelihoods of the poor at the cost of saving too few lives. Most have erred on the side of saving lives first others that let livelihoods predominate thinking (the US, UK) are being castigated for subjecting their people to heavy losses of life. Almost no country in the world has got the mix right. In the current covid-19 pandemic, it is difficult to decide between lives and livelihoods, and also the right juncture at which livelihoods have to become more important than merely saving lives.

While some choices are easy to make, like helping the needy when state resources are adequate to do so, in many other situations, the choices are difficult. The real value of the Ramayana and Mahabharata is that they present, in stark outline, the difficult public policy choices faced by people, nations and leaders. In 1947, India accepted partition for peace, but this did not prevent future wars between the partitioned nations. But in the end, partition did not prevent the Kurukshetra war. In an effort to keep the peace, Bhishma and Dhritarashtra decide to partition the kingdom by hiving off Indraprastha to the Pandavas. In the 20th century, Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah seem to have agreed that partition was better than civil war. Then there is that ultimate moral dilemma that Shri Krishna expounds in the Bhagavad Gita: at what point does the desire for peace trump war, and vice-versa? In the 19th century, Abraham Lincoln decided that civil war was better than compromise with slavery.

Was Bhishma right to believe that dharma required him to maintain his vow of celibacy, made in a moment of extreme commitment to his father, long after his father had passed? Did Bhishma deny Hastinapur the right to have a good and competent ruler when it was only his personal ego (to stick to his vow of celibacy) standing between him and the prevention of a fratricidal war between the Kauravas and Pandavas?

The moral dilemmas presented in the Mahabharata are even starker.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)